By Maria Gregorio

Harlem has been undoubtably a central location of artistic and cultural connection. It has also become not only a geographic location, but a symbol and a birthplace of an artistic movement, one that intersects with Black racial and cultural identity beyond Harlem.[i] Author Emily Bernard notes that African and African American art forms evolved during slavery and continued to do so after Emancipation when a collective Black American identity was born. An identity initiated as a way to correct negative racial stereotypes; it was called “The New Negro”.

The infamous Harlem Renaissance in its own time was called The New Negro Movement. Its original name suggests the importance of Black racial identity to the Renaissance and its creators. The return of Black soldiers from WWI after fighting for American interests overseas also fueled a renewed sense amongst African Americans to advocate for equality in their own country. According to Bernard, prior to this there had not been any opportunity for African Americans to take on the project of national identity to this intensity.[ii] There were also other concurrent socio-political components influencing the Renaissance, such as the Great Migration, pan-African congresses, Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association and others.[iii]

By the mid-1920’s, debate began between intellectuals about the function of art: art for art’s sake or art for propaganda. W. E. B. Du Bois felt strongly about art as a tool of propaganda, particularly because of dehumanizing stories and images in which Black people were portrayed in the mainstream. Such stories influenced how racism was justified, and sociologists argued that this also impacted self-image. Charles S. Johnson and Du Bois believed that artistic achievement would lead to racial pride, positive self-image, confidence, and how Black people saw themselves. They also argued that this would in turn change how Black people were treated by whites and white society.

Unfortunately, Du Bois’s perspective did not take into account the economic and social inequality deeply embedded between Blacks and whites in America. Pearson argues it was unrealistic to aim for change in white attitudes towards Blacks; not only because few whites knew about Black art, but because whites were not ready to grant Blacks the “distribution of talent and mediocrity that characterizes other races.” [iv]

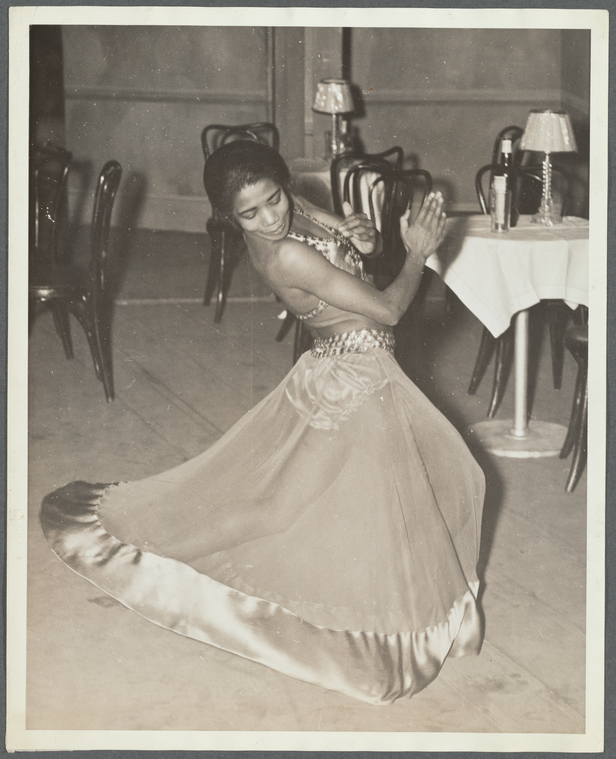

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division,

New York Public Library Digital Archives

Ironically, the popularity of Harlem has another layer which has been discussed by many scholars and artists. Bernard describes this as “white fascination of black primitivism“ and “white spectatorship” as well as appropriation to be prevalent in African American history. As such, the Black community has had minimal benefits from this trend. This was seen in how the Harlem Renaissance received white institutional support and became “in vogue” while Black communities continued to live in poor conditions.[v]

In the time of the Renaissance, Black “self-image” was not only up against the recent history of slavery, but the ongoing racial violence of lynchings, other activities of the Ku Klux Klan, and minstrel shows. Minstrel shows exhibited degrading racial stereotypes which were marketed as entertainment and humor of Blacks and people of African descent. Such images fed into the realities of physical and psychological violence perpetuated towards Black and African American people in a country that preached freedom, equality, and Christian values.

Du Bois and other intellectuals argued that by using art as propaganda to uplift the Black collective, and if Blacks raised their racial image and aimed for achievement, equality could be obtained because they would be seen as human by white society.[vi] Unfortunately although this concept was hopeful and true to some degree, it placed focus on Black people to change racist society, rather than insisting that all people, especially whites, be held responsible for this change.

The Black community in Harlem and across the U.S. suffered significantly during the Great Depression, including Black artists. And yet Black entertainment in Harlem became increasingly “vogue” to white audiences. Nightclubs, live music performances, and cabarets thrived. White people travelled long distances to be audiences where Black people could only serve as workers or perform. White owners of the venues, including The Cotton Club, imposed additional restrictions: only Black people of light skin tones were allowed to work there.

Within an artistic and cultural movement, there persisted a racially-based economic inequality and a colorism structure. Systematic colorism was another form of racial oppression which allowed some Black people, of light skin, to earn income with the limitations and restrictions set forth by white businessmen. Women were additionally marginalized by their gender, and to work and to perform on stage required one to be light-skinned.[vii] This was another way in which opportunity, money and beauty were attributed to light skin.

In spite of artistic achievements, racist and patronizing concepts toward Black people have continued. Stereotypes persisted in literature, entertainment, and exoticization continued in the Harlem nightlife. Harlem also became a place where whites sought sexual thrills.[viii]

Although the Harlem Renaissance was seen as a “failure” by writers and scholars alike for these reasons, it’s hard to imagine the arts today without the contributions of the artists of the era. Their global influence extends beyond who most of us know as household names— Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and countless others. It’s worth questioning how we view success and failure in the context of the racial and social inequalities in America.

Black artists of the Harlem Renaissance not only represent themselves. They represent their stories and lineage of survival. Black artists have offered a perspective beyond a European and white narrative and as a result other marginalized people, including people of color, can see themselves in these stories in ways which dominant art and narratives may not offer.

Through stories, poetry, visual arts, dance, music, Black artists have shown the beauty of embracing one’s own racial and cultural identity by either the art form and/or representation. Some scholars have called this cultural pluralism. Whether art be for propaganda or for art’s sake, the identity of an artist can be seen in their work, their interviews, their narratives, and in their images. And this intersection of art and identity is cause for celebration.

“Dance is the fist with which I will fight the scheming ignorance of prejudice.”

—Pearl Primus

The Legacy of Black Female Performance Artists of the Renaissance

By Maria Gregorio

There has been little recognition of Black women artists in the Harlem Renaissance. Female authors, poets, dancers, musicians, pioneers and activists do not carry the notoriety of Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, or Duke Ellington. Along with racism, Black female artists endured gender discrimination, sexual assault and misogyny throughout their lives while continuing to work in their art form. Many worked low-wage jobs and raised children. To this day the Renaissance remains largely associated with Alain Locke, W. E. B. De Bois, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and other male authors and intellects.

For women of color like myself, the achievements of Black women who have come before us have opened the door not only through the battle for civil rights and achievement in the male-dominated world of the arts and letters, but also in the creative mind. They have shown us an intimate image of women and complex narratives of those who have been marginalized. They have demonstrated by example their importance. They also show truthfully, that it was never an easy road to their success and survival. With all this in mind, their achievement all the more essential to know and to honor.

Examples of how women broke the constraints of oppression by living as they pleased are countless. Author and historian Saidiya Hartman profiles specific women who defied society’s violence, bigotry and gender bias by living their lives as fully and as freely as they could.[ix]

Source: New York Public Library

Dance is an art form that stretches itself from the nightclub to stage performances; from the non-professional to the professional realms of dance. During the Harlem Renaissance, the latter was deemed to be “Western high art”. Cabarets or nightclub dancing often involved the Slow Drag or Lindy Hop, where couples were either sensually entwined together or doing flips over one another. Although these dances evolved into competitions, they were typically not be considered “art” by intellectuals or mainstream society of the Renaissance era.

As a young woman in my early twenties, I went to nightclubs frequently with my friends and found dancing to be a respite from the sense of isolation I experienced growing up as an immigrant woman of color in predominantly white communities. Dance was also the way I found a sense of community and developed a sense of pride in my own body. Pearl Primus believed through dance, healing and resilience emerges naturally from the physical body.[x]

During the Renaissance, dancing was a way many women and men found respite. Women moved against restrictions placed on them and found solace through dance. There are three in particular whose impact in the performance world were unique and significant.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by author and scholar Saidiya Hartman describes the lives of Black women who lived outside of cultural norms, including women who became dancers and were part of the nightlife of Harlem from early 1900’s up to the 1940’s. In the case of dance, many artists spent time and performed in nightclubs before they reached the stage. The life journey of dancer and performer Mabel Hampton is one example of a largely unrecognized yet significant Black lesbian woman of the Renaissance. She too, was part of the nightlife where many people sought solace.

When Ms. Hampton was seventeen years old, she moved to Harlem to work and to further explore singing and dancing. By this time she was already a survivor of childhood trauma from rape and abuse by her uncle, had run away from home, and was doing domestic work to make ends meet. Hampton met Mildred Mitchell as a child, who became a mother figure to her and encouraged her to audition for chorus in a musical revue in Coney Island.

Hampton did not aim for marriage and children as what was expected of women of the time. As she made friends and spent time in dance halls and watched performances, she realized that she wanted to be a dancer. During this period she lived on 122nd Street near 7th Avenue, which was known as “Black Broadway,” a primarily Black community teeming with activity. Hartman describes the typical scene at the time to be a blend of activists street preaching, Southern migrants selling yams and pigs feet, women selling sex, children playing in the street, laborers travelling between work and home, and finely dressed couples walking through.

Hartman describes choreographed dance “a call to freedom;” as a way “not to be fixed in the bottom, not to be walled in the ghetto” and nightclubs as “escape from the dull routine of work” (Hartman 305-306). Cabarets were smaller venues than chorus stage performances and required improvisation. Hampton and her friends performed in cabarets in a time when women like them were profiled by police and deemed to be prostitutes. It was also a time when Harlem was known for white people seeking “illicit sexual thrills.”[xi]

Mabel Hampton came of age in Harlem. Her intimate and sexual relationships with women led her to meet other artists, actors and musicians. In 1924 Hampton began her chorus role in Come Along, Mandy. The show was successful with Black and white audiences and received notoriety at the time from critics. She continued to dance and attended performances and soon discovered Florence Mills.

Florence Mills performed in nightclubs for a time before her Off-Broadway role in Shuffle Along in 1921. She became famous for her compelling voice as well as stage and dance presence, and her performances were integrated with jazz music. Langston Hughes believed this musical initiated the Harlem Renaissance and popularity of Black entertainment into mainstream white audiences and becoming “in vogue.”[xii]

Mills performed throughout the U.S. and gained notoriety. In spite of the recognition for her talent from white audiences, she faced racism from white peers in show business. Mills was offered to perform a role in Greenwich Village Follies and the rest of the cast was resentful for it and threatened to walk off the production.

Mills turned down a role in Ziegfeld Follies in order to form an all-Black cast, which led to a successful musical comedy, From Dixie to Broadway, which was performed in Broadhurst Theatre in New York City. Mills was set to perform in Blackbirds of 1928 in Harlem but died an untimely death at age 31 from complications related to appendicitis.

In addition to her stellar voice and performances, Mills was known for the ways in which she used her art form and influence to break the restrictions and barriers placed against Black people in America. She worked tirelessly on stage; her first musical alone totaled more than five hundred performances. Unfortunately, there are no existing records of any her performances.

More than one hundred and fifty thousand people attended Ms. Hills’s funeral. Duke Ellington dedicated his song “Firewater” and later re-recorded and renamed it, “Black Beauty” in dedication to Florence Mills.[xiii]

Another strong figure of the Renaissance with little recognition to date is Pearl Primus. Ms. Primus was a scholar, anthropologist, and dancer who brought African dance to America. Born in Trinidad, she immigrated to New York City with her parents as a child in 1921. After graduating from Hunter College in 1940 and deciding to forgo medical school as a result of discrimination experienced, she pursued dance and received a scholarship to the New Dance Group in 1942. She became known for her remarkable “airborne leaps” on stage as well as the range and repertoire of her talent, which included modern dance, African dance and drumming, and swing dance.[xiv]

Mills, Hampton and Primus did not separate their art form from their racial identity. In this sense their artistic expression was both political and groundbreaking. Primus also performed in nightclubs early in her life, namely at Café Society in downtown Manhattan. At Café Society, she gained the support of Lina Horne, Billie Holiday, Paul Robeson and many others (Dance Journal 5). She also became politically involved in the civil rights movement. Her life and art form intertwined with the movement towards racial pride and equality.

In order to develop her dance repertoire, Primus did extensive research in the American South and in Africa. Early in her career in 1944, to immerse herself in a deep understanding of migrant workers in the South as a way to inform her work, Primus posed as a migrant worker in Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina and picked cotton. She pursued her own learning from books about African dance, and in 1948 she received a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation to further her research and subsequently travelled alone to various countries in Africa.

Primus later completed her PhD in anthropology at NYU in 1978. Through teaching, performances, and research, she integrated her interests and experiences and claimed dance as a vital language that connects all people and cultures. She challenged the term “primitive” and other negative assumptions about Africa and African dance. She taught both dance and anthropology in various colleges and received numerous awards and honors. As dancer, educator, and anthropologist, Primus made a remarkable societal impact in her lifetime.

These are obviously brief excerpts about the life experiences and contributions of three exceptional women. I encourage everyone to engage in further reading and research, beginning with the references below. Every artist and admirer of the arts should know about them, as well as of the full magnitude of the Harlem Renaissance.

“The dancer is the conductor, the wire which connects the earth and sky.”

—Pearl Primus

References

[i] Mitchell, Ernest Julius. “‘Black Renaissance’: A Brief History of the Concept.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 55, no. 4, 2010, pp. 641–665. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41158720. Accessed 16 May 2020.

[ii] Bernard, Emily. “The Renaissance and the Vogue.” The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, edited by G. Hutchinson, Cambridge Companions to Literature, pp. 28-40. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL052185699X.003

[iii] Hutchinson, George. “Introduction.” The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, edited by George Hutchinson, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp. 1–10. Cambridge Companions to Literature.

[iv] Pearson, Ralph I. “Combatting Racism with Art: Charles S. Johnson and the Harlem Renaissance.” American Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1977, pp. 123–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40641261. Accessed 22 Mar. 2020.

[v] Abdul-Jabaar, Kareem. On The Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through The Harlem Renaissance. Cited from: Siegal, Robert. “The Harlem Renaissance, On and Off the Court.” npr.org, 2007, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7032039. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

[vi] W. E. B. Du Bois. “The Criteria of Negro Art.” The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader, edited by David L. Lewis, New York: Penguin Books, 1995, pp. 100-105.

[vii] Hartman, Saidiya (2019). The Beauty of the Chorus. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval(297-343). W.W. Norton & Company.

[viii] Osofsky, Gilbert. “Symbols of the Jazz Age: The New Negro and Harlem Discovered.” American Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 2, 1965, pp. 229–238. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2711356. Accessed 16 May 2020.

[ix] Hartman, Saidiya (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval. W.W. Norton & Company.

[x] “Pearl in Our Midst: Pearl Primus (November 29, 1919-October 29, 1994).” Dance Research Journal, vol. 27, no. 1, 1995, pp. 80–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478451. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

[xi] Hutchinson, George. “Harlem Renaissance: American Literature and Art.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Harlem-Renaissance-American-literature-and-art, 2019. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

[xii] “Florence Mills.” Notable Black American Women, Gale, 1992. Gale In Context: Biography, https://link-galecom.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/K1623000301/BIC?u=nypl&sid=BIC&xid=1c6b1c6d. Accessed 30 Mar. 2020. Gale Document Number: GALE|K1623000301 – NYPL

[xiii] Florence Mills. 26 March 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Mills. Accessed 3 April 2020.

[xiv] “Pearl in Our Midst: Pearl Primus (November 29, 1919-October 29, 1994).” Dance Research Journal, vol. 27, no. 1, 1995, pp. 80–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478451. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

Other References Used & Further reading:

Perpener, John. “Dance, Difference, and Racial Dualism at the Turn of the Century.” Dance Research Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2000, pp. 63–69. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478277. Accessed 21 Apr. 2020.

Tanner, Jo. “Shuffle Along: The Musical at the Center of the Harlem Renaissance.” Drop Me Off in Harlem: Exploring the Intersections, 2003. http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/interactives/harlem/themes/shufflealong.html. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

Nestle, Joan. “Excerpts from the Oral History of Mabel Hampton.” Signs, vol. 18, no. 4, 1993, pp. 925–935. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3174913. Accessed 5 Apr. 2020.

Valentin, Wilson. “Faculty Q&A: Professor Farah Griffin Examines Three Pioneering Women Artists in 1940s Harlem,” Columbia News, 2013. https://news.columbia.edu/news/faculty-qa-professor-farah-griffin-examines-three-pioneering-women-artists-1940s-harlem. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.