By Maria Gregorio

There has been little recognition of Black women artists in the Harlem Renaissance. Female authors, poets, dancers, musicians, pioneers and activists do not carry the notoriety of Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, or Duke Ellington. Along with racism, Black female artists endured gender discrimination, sexual assault and misogyny throughout their lives while continuing to work in their art form. Many worked low-wage jobs and raised children. To this day the Renaissance remains largely associated with Alain Locke, W. E. B. De Bois, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and other male authors and intellects.

For women of color like myself, the achievements of Black women who have come before us have opened the door not only through the battle for civil rights and achievement in the male-dominated world of the arts and letters, but also in the creative mind. They have shown us an intimate image of women and complex narratives of those who have been marginalized. They have demonstrated by example their importance. They also show truthfully, that it was never an easy road to their success and survival. With all this in mind, their achievement all the more essential to know and to honor.

Examples of how women broke the constraints of oppression by living as they pleased are countless. Author and historian Saidiya Hartman profiles specific women who defied society’s violence, bigotry and gender bias by living their lives as fully and as freely as they could.[ix]

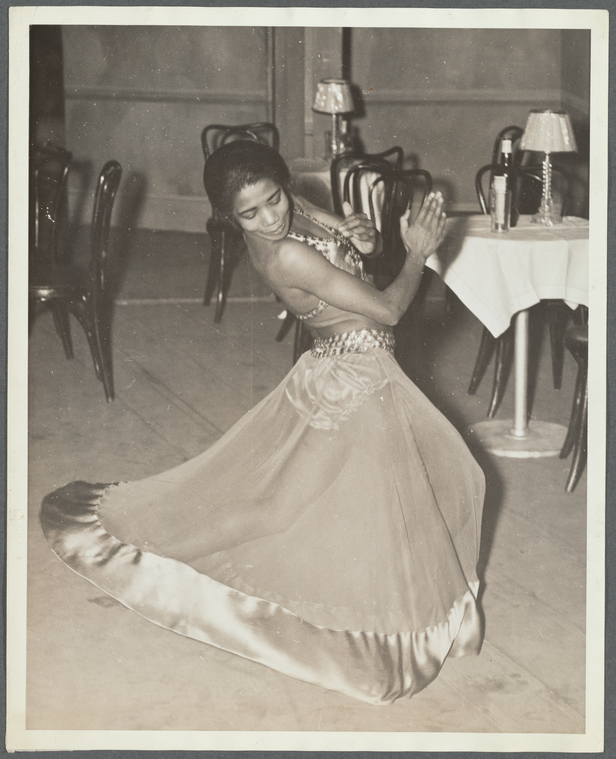

Source: New York Public Library

Dance is an art form that stretches itself from the nightclub to stage performances; from the non-professional to the professional realms of dance. During the Harlem Renaissance, the latter was deemed to be “Western high art”. Cabarets or nightclub dancing often involved the Slow Drag or Lindy Hop, where couples were either sensually entwined together or doing flips over one another. Although these dances evolved into competitions, they were typically not be considered “art” by intellectuals or mainstream society of the Renaissance era.

As a young woman in my early twenties, I went to nightclubs frequently with my friends and found dancing to be a respite from the sense of isolation I experienced growing up as an immigrant woman of color in predominantly white communities. Dance was also the way I found a sense of community and developed a sense of pride in my own body. Pearl Primus believed through dance, healing and resilience emerges naturally from the physical body.[x]

During the Renaissance, dancing was a way many women and men found respite. Women moved against restrictions placed on them and found solace through dance. There are three in particular whose impact in the performance world were unique and significant.

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by author and scholar Saidiya Hartman describes the lives of Black women who lived outside of cultural norms, including women who became dancers and were part of the nightlife of Harlem from early 1900’s up to the 1940’s. In the case of dance, many artists spent time and performed in nightclubs before they reached the stage. The life journey of dancer and performer Mabel Hampton is one example of a largely unrecognized yet significant Black lesbian woman of the Renaissance. She too, was part of the nightlife where many people sought solace.

When Ms. Hampton was seventeen years old, she moved to Harlem to work and to further explore singing and dancing. By this time she was already a survivor of childhood trauma from rape and abuse by her uncle, had run away from home, and was doing domestic work to make ends meet. Hampton met Mildred Mitchell as a child, who became a mother figure to her and encouraged her to audition for chorus in a musical revue in Coney Island.

Hampton did not aim for marriage and children as what was expected of women of the time. As she made friends and spent time in dance halls and watched performances, she realized that she wanted to be a dancer. During this period she lived on 122nd Street near 7th Avenue, which was known as “Black Broadway,” a primarily Black community teeming with activity. Hartman describes the typical scene at the time to be a blend of activists street preaching, Southern migrants selling yams and pigs feet, women selling sex, children playing in the street, laborers travelling between work and home, and finely dressed couples walking through.

Hartman describes choreographed dance “a call to freedom;” as a way “not to be fixed in the bottom, not to be walled in the ghetto” and nightclubs as “escape from the dull routine of work” (Hartman 305-306). Cabarets were smaller venues than chorus stage performances and required improvisation. Hampton and her friends performed in cabarets in a time when women like them were profiled by police and deemed to be prostitutes. It was also a time when Harlem was known for white people seeking “illicit sexual thrills.”[xi]

Mabel Hampton came of age in Harlem. Her intimate and sexual relationships with women led her to meet other artists, actors and musicians. In 1924 Hampton began her chorus role in Come Along, Mandy. The show was successful with Black and white audiences and received notoriety at the time from critics. She continued to dance and attended performances and soon discovered Florence Mills.

Florence Mills performed in nightclubs for a time before her Off-Broadway role in Shuffle Along in 1921. She became famous for her compelling voice as well as stage and dance presence, and her performances were integrated with jazz music. Langston Hughes believed this musical initiated the Harlem Renaissance and popularity of Black entertainment into mainstream white audiences and becoming “in vogue.”[xii]

Mills performed throughout the U.S. and gained notoriety. In spite of the recognition for her talent from white audiences, she faced racism from white peers in show business. Mills was offered to perform a role in Greenwich Village Follies and the rest of the cast was resentful for it and threatened to walk off the production.

Mills turned down a role in Ziegfeld Follies in order to form an all-Black cast, which led to a successful musical comedy, From Dixie to Broadway, which was performed in Broadhurst Theatre in New York City. Mills was set to perform in Blackbirds of 1928 in Harlem but died an untimely death at age 31 from complications related to appendicitis.

In addition to her stellar voice and performances, Mills was known for the ways in which she used her art form and influence to break the restrictions and barriers placed against Black people in America. She worked tirelessly on stage; her first musical alone totaled more than five hundred performances. Unfortunately, there are no existing records of any her performances.

More than one hundred and fifty thousand people attended Ms. Hills’s funeral. Duke Ellington dedicated his song “Firewater” and later re-recorded and renamed it, “Black Beauty” in dedication to Florence Mills.[xiii]

Another strong figure of the Renaissance with little recognition to date is Pearl Primus. Ms. Primus was a scholar, anthropologist, and dancer who brought African dance to America. Born in Trinidad, she immigrated to New York City with her parents as a child in 1921. After graduating from Hunter College in 1940 and deciding to forgo medical school as a result of discrimination experienced, she pursued dance and received a scholarship to the New Dance Group in 1942. She became known for her remarkable “airborne leaps” on stage as well as the range and repertoire of her talent, which included modern dance, African dance and drumming, and swing dance.[xiv]

Mills, Hampton and Primus did not separate their art form from their racial identity. In this sense their artistic expression was both political and groundbreaking. Primus also performed in nightclubs early in her life, namely at Café Society in downtown Manhattan. At Café Society, she gained the support of Lina Horne, Billie Holiday, Paul Robeson and many others (Dance Journal 5). She also became politically involved in the civil rights movement. Her life and art form intertwined with the movement towards racial pride and equality.

In order to develop her dance repertoire, Primus did extensive research in the American South and in Africa. Early in her career in 1944, to immerse herself in a deep understanding of migrant workers in the South as a way to inform her work, Primus posed as a migrant worker in Georgia, Alabama, and South Carolina and picked cotton. She pursued her own learning from books about African dance, and in 1948 she received a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation to further her research and subsequently travelled alone to various countries in Africa.

Primus later completed her PhD in anthropology at NYU in 1978. Through teaching, performances, and research, she integrated her interests and experiences and claimed dance as a vital language that connects all people and cultures. She challenged the term “primitive” and other negative assumptions about Africa and African dance. She taught both dance and anthropology in various colleges and received numerous awards and honors. As dancer, educator, and anthropologist, Primus made a remarkable societal impact in her lifetime.

These are obviously brief excerpts about the life experiences and contributions of three exceptional women. I encourage everyone to engage in further reading and research, beginning with the references below. Every artist and admirer of the arts should know about them, as well as of the full magnitude of the Harlem Renaissance.

“The dancer is the conductor, the wire which connects the earth and sky.”

—Pearl Primus

References

[i] Mitchell, Ernest Julius. “‘Black Renaissance’: A Brief History of the Concept.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 55, no. 4, 2010, pp. 641–665. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41158720. Accessed 16 May 2020.

[ii] Bernard, Emily. “The Renaissance and the Vogue.” The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, edited by G. Hutchinson, Cambridge Companions to Literature, pp. 28-40. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL052185699X.003

[iii] Hutchinson, George. “Introduction.” The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, edited by George Hutchinson, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp. 1–10. Cambridge Companions to Literature.

[iv] Pearson, Ralph I. “Combatting Racism with Art: Charles S. Johnson and the Harlem Renaissance.” American Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 1977, pp. 123–134. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40641261. Accessed 22 Mar. 2020.

[v] Abdul-Jabaar, Kareem. On The Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through The Harlem Renaissance. Cited from: Siegal, Robert. “The Harlem Renaissance, On and Off the Court.” npr.org, 2007, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7032039. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

[vi] W. E. B. Du Bois. “The Criteria of Negro Art.” The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader, edited by David L. Lewis, New York: Penguin Books, 1995, pp. 100-105.

[vii] Hartman, Saidiya (2019). The Beauty of the Chorus. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval(297-343). W.W. Norton & Company.

[viii] Osofsky, Gilbert. “Symbols of the Jazz Age: The New Negro and Harlem Discovered.” American Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 2, 1965, pp. 229–238. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2711356. Accessed 16 May 2020.

[ix] Hartman, Saidiya (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval. W.W. Norton & Company.

[x] “Pearl in Our Midst: Pearl Primus (November 29, 1919-October 29, 1994).” Dance Research Journal, vol. 27, no. 1, 1995, pp. 80–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478451. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

[xi] Hutchinson, George. “Harlem Renaissance: American Literature and Art.” Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/event/Harlem-Renaissance-American-literature-and-art, 2019. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

[xii] “Florence Mills.” Notable Black American Women, Gale, 1992. Gale In Context: Biography, https://link-galecom.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/K1623000301/BIC?u=nypl&sid=BIC&xid=1c6b1c6d. Accessed 30 Mar. 2020. Gale Document Number: GALE|K1623000301 – NYPL

[xiii] Florence Mills. 26 March 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Mills. Accessed 3 April 2020.

[xiv] “Pearl in Our Midst: Pearl Primus (November 29, 1919-October 29, 1994).” Dance Research Journal, vol. 27, no. 1, 1995, pp. 80–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478451. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.

Other References Used & Further reading:

Perpener, John. “Dance, Difference, and Racial Dualism at the Turn of the Century.” Dance Research Journal, vol. 32, no. 1, 2000, pp. 63–69. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1478277. Accessed 21 Apr. 2020.

Tanner, Jo. “Shuffle Along: The Musical at the Center of the Harlem Renaissance.” Drop Me Off in Harlem: Exploring the Intersections, 2003. http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/interactives/harlem/themes/shufflealong.html. Accessed 25 Mar. 2020.

Nestle, Joan. “Excerpts from the Oral History of Mabel Hampton.” Signs, vol. 18, no. 4, 1993, pp. 925–935. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3174913. Accessed 5 Apr. 2020.

Valentin, Wilson. “Faculty Q&A: Professor Farah Griffin Examines Three Pioneering Women Artists in 1940s Harlem,” Columbia News, 2013. https://news.columbia.edu/news/faculty-qa-professor-farah-griffin-examines-three-pioneering-women-artists-1940s-harlem. Accessed 29 Mar. 2020.