Hedayat Reda

Zora Neale Hurston

She smiled at me from a photograph at the Schomburg Center, her dark eyes showing just a hint of mischief and playfulness. I knew who it was even before the research assistant said, “Zora Neale Hurston.” Not because I had ever seen a photograph of her before, but because—I imagined—that she was the sole female figure of the Harlem Renaissance that could have a look like that. Sassy and knowing. Like she was certain that she was here to stay.

It made me upset to discover—on choosing “Zora’s life” as my research topic for a class project—that she had not actually stayed. That she had— in fact—been forgotten, for a very long time.

How could a writer like that, a trail blazer of the 1920s, just disappear?

When I was younger, I thought that stories lived forever. That writers, the creators of stories, could not die, because they lived on in their stories. That is why I wanted to become a writer. I wanted to touch as many lives as possible…even when I was gone. It wasn’t until I started researching Zora Neale Hurston’s life that I discovered that the lives we live are many and cannot be defined through our writing. Also, that we writers don’t know who we will touch or how we will touch them until we are gone.

This is a story about Zora the person and how she came to speak to me.

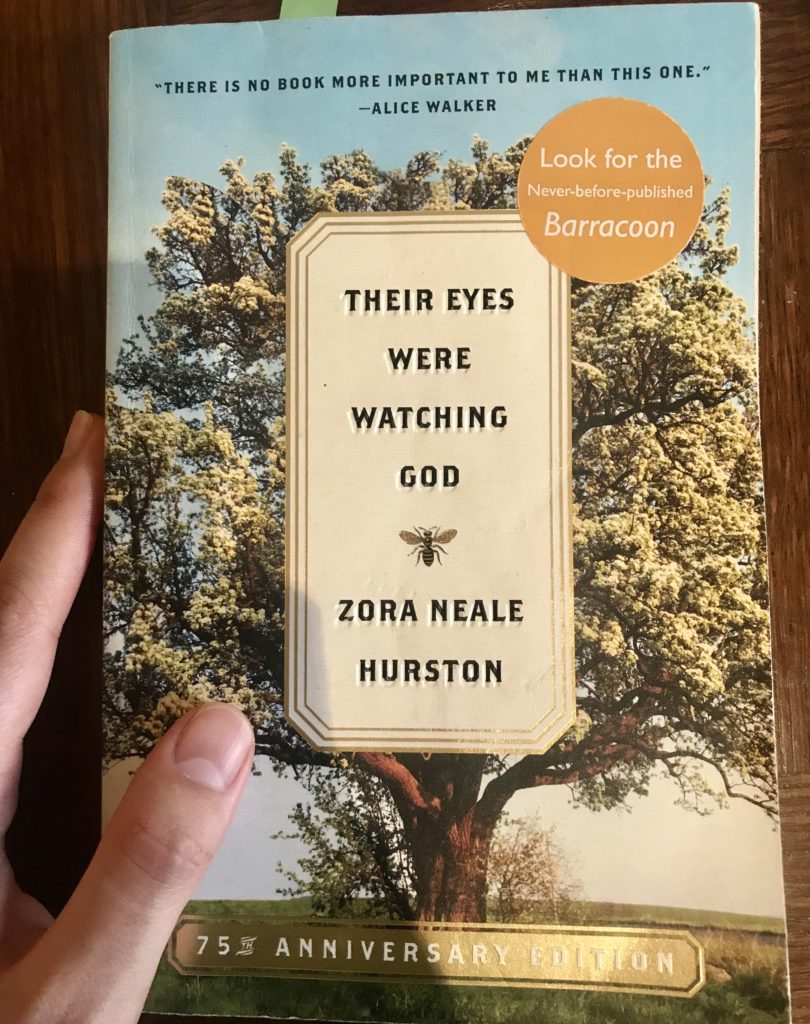

It started with a copy of Their Eyes Were Watching God that I found in a bookstore many years ago. I had no idea who Zora Neale Hurston was or what this book was about at the time, but I really liked the title and felt like this book had something to say to me. Coincidentally, I was also reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple around this time. I was going through an Oprah phase and came across an interview of hers where she talks about the impact that Walker’s novel had on her life (and the somewhat miraculous story of how she got the part of Sofia in the movie… Google it!). At the time, I didn’t know that there was any connection between both writers. If someone would have asked me, I would have said, “I guess they’re both writing about the South.” But I would later discover that Walker played a pivotal role in Hurston’s life, in how she is remembered. And vice versa.

I never got through Their Eyes. I found the Southern accent Hurston wrote it in to be too confusing and hard to keep up with. But it always stayed there on my shelf, taunting me, as if to say: “you must read me.”

When I started researching Zora Neale Hurston for a project about art and the Harlem Renaissance, I had no clue what I would find. I knew that Hurston had been a prominent writer of the Harlem Renaissance and that she had belonged to a group of Harlem writers that called themselves the Literati (or Niggerati, as Hurston referred to them). I also knew that she was from the South, originally. Other than that, I was clueless. I was also not very curious, unfortunately. Not being from the South, or even American, I didn’t really care that much about race-as a topic- or what Hurston’s writing might stand for in America. Nonetheless, something about her character, intrigued me. I was interested to know more about this Southern writer who had risen to the top of Renaissance writing and then disappeared from literature for 40 or so years. What had happened?

This time, I wouldn’t give up on her so easily.